Foreword

I am pleased to present the Annual Cyber Threat Report 2022–23 developed by the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD).

As the Defence Strategic Review made clear, in the post-Second World War period Australia was protected by its geography and the limited ability of other nations in the region to project combat power. In the current strategic era, Australia’s geographic advantages have been eroded as more countries have enhanced their ability to project combat power across greater ranges, including through the rapid development of cyber capabilities.

Australia’s region, the Indo-Pacific, is also now seeing growing competition on multiple levels – economic, military, strategic and diplomatic – framed by competing values and narratives.

In this context, Australian governments, critical infrastructure, businesses and households continue to be the target of malicious cyber actors. This report illustrates that both state and non-state actors continue to show the intent and capability to compromise Australia’s networks. It also highlights the added complexity posed by emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence.

The report demonstrates the persistent threat that state cyber capabilities pose to Australia. This threat extends beyond cyber espionage campaigns to disruptive activities against Australia’s essential services. The report also confirms that the borderless and multi-billion dollar cybercrime industry continues to cause significant harm to Australia, with Australians remaining an attractive target for cybercriminal syndicates around the world.

Through case studies, the report demonstrates the persistence and tenacity of these cyber actors. It shows that these adversaries constantly test vulnerabilities in Australia’s cyber ecosystem and employ a range of techniques to evade Australia’s cyber defences.

The threat environment characterised in this report underscores the importance of ASD’s work in defending Australia’s security and prosperity. It also reinforces the significance of the Australian Government’s investment in ASD’s cyber and intelligence capabilities under Project REDSPICE (Resilience, Effects, Defence, Space, Intelligence, Cyber, Enablers).

It is clear we must maintain an enduring focus on cyber security in Australia. The Australian Government is committed to leading our nation’s efforts to bolster our cyber resilience.

We also know that the best cyber defences are founded on genuine partnerships between and across the public and private sectors. The development of this report, which draws on insights from across the Commonwealth Government, our international partners, Australian industry and the community, is a testament to this collaboration.

This report presents a clear picture of the cyber threat landscape we face and is a vital part of Australia’s collective efforts to enhance our cyber resilience.

The Hon Richard Marles, MP

Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence

About ASD’s ACSC

ASD’s Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) is the Australian Government’s technical authority on cyber security. The ACSC brings together capabilities to improve Australia’s national cyber resilience and its services include:

- the Australian Cyber Security Hotline, which is contactable 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, via 1300 CYBER1 (1300 292 371)

- publishing alerts, technical advice, advisories and notifications on significant cyber security threats

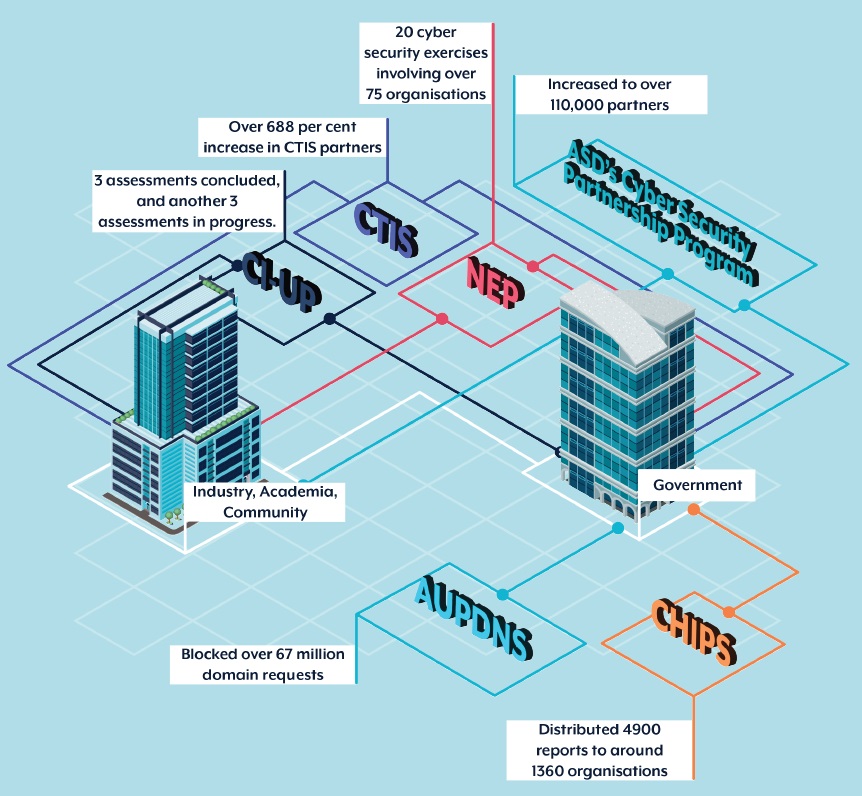

- cyber threat monitoring and intelligence sharing with partners, including through the Cyber Threat Intelligence Sharing (CTIS) platform

- helping Australian entities respond to cyber security incidents

- exercises and uplift activities to enhance the cyber security resilience of Australian entities

- supporting collaboration between over 110,000 Australian organisations and individuals on cyber security issues through ASD’s Cyber Security Partnership Program.

The most effective cyber security is collaborative and partnerships are key to this work. ASD thanks all of the organisations that contributed to this report. This includes Australian local, state, territory and federal government agencies, and industry partners.

Executive summary

Malicious cyber activity continued to pose a risk to Australia’s security and prosperity in the FY 2022-23. A range of malicious cyber actors showed the intent and capability needed to compromise vital systems, and Australian networks were regularly targeted by both opportunistic and more deliberate malicious cyber activity.

ASD responded to over 1,100 cyber security incidents from Australian entities. Separately, nearly 94,000 reports were made to law enforcement through ReportCyber – around one every 6 minutes.

ASD identified a number of key cyber security trends in FY 2022–23:

State actors focused on critical infrastructure – data theft and disruption of business.

Globally, government and critical infrastructure networks were targeted by state cyber actors as part of ongoing information-gathering campaigns or disruption activities. The AUKUS partnership, with its focus on nuclear submarines and other advanced military capabilities, is likely a target for state actors looking to steal intellectual property for their own military programs. Cyber operations are increasingly the preferred vector for state actors to conduct espionage and foreign interference.

In 2022–23, ASD joined international partners to call out Russia’s Federal Security Service’s use of ‘Snake’ malware for cyber espionage, and also highlighted activity associated with a People’s Republic of China state-sponsored cyber actor that used ‘living-off-the-land’ techniques to compromise critical infrastructure organisations.

Australian critical infrastructure was targeted via increasingly interconnected systems.

Operational technology connected to the internet and into corporate networks has provided opportunities for malicious cyber actors to attack these systems. In 2022–23, ASD responded to 143 cyber security incidents related to critical infrastructure.

Cybercriminals continued to adapt tactics to extract maximum payment from victims.

Cybercriminals constantly evolved their operations against Australian organisations, fuelled by a global industry of access brokers and extortionists. ASD responded to 127 extortion-related incidents: 118 of these incidents involved ransomware or other forms of restriction to systems, files or accounts. Business email compromise remained a key vector to conduct cybercrime. Ransomware also remained a highly destructive cybercrime type, as did hacktivists’ denial-of-service attacks, impacting organisations’ business operations.

Data breaches impacted many Australians.

Significant data breaches resulted in millions of Australians having their information stolen and leaked on the dark web.

One in 5 critical vulnerabilities was exploited within 48 hours.

This was despite patching or mitigation advice being available. Malicious cyber actors used these critical flaws to cause significant incidents and compromise networks, aided by inadequate patching.

Cyber security is increasingly challenged by complex ICT supply chains and advances in fields such as artificial intelligence. To boost cyber security, Australia must consider not only technical controls such as ASD’s Essential Eight, but also growing a positive cyber-secure culture across business and the community. This includes prioritising secure-by-design and secure-by-default products during both development (vendors) and procurement (customers).

ASD’s first year of REDSPICE increased cyber threat intelligence sharing, the uplift of critical infrastructure, and an enhanced 24/7 national incident response capability.

Genuine partnerships across both the public and private sectors have remained essential to Australia’s cyber resilience; and ASD’s Cyber Security Partnership Program has grown to include over 110,000 organisations and individuals.

Year in review

What ASD saw

Average cost of cybercrime per report, up 14 per cent

- small business: $46,000

- medium business: $97,200

- large business: $71,600.

Nearly 94,000 cybercrime reports, up 23 per cent

- on average a report every 6 minutes

- an increase from 1 report every 7 minutes.

Answered over 33,000 calls to the Australian Cyber Security Hotline, up 32 per cent

- on average 90 calls per day

- an increase from 69 calls per day.

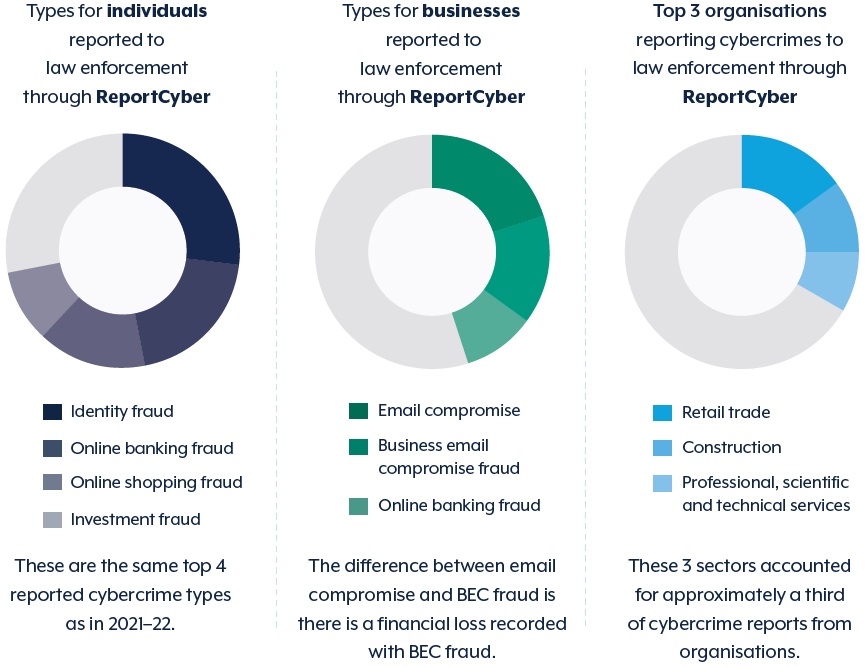

Top 3 cybercrime types for individuals

- identity fraud

- online banking fraud

- online shopping fraud.

Top 3 cybercrime types for business

- email compromise

- business email compromise (BEC) fraud

- online banking fraud.

Publicly reported common vulnerabilities and exposures (CVEs) increased 20 per cent.

What ASD did

- Responded to over 1,100 cyber security incidents, similar to last year.

- 10 per cent of all incidents responded to included ransomware, similar to last year.

- Notified 158 entities of ransomware activity on their networks, compared to 148 last year, roughly a 7 per cent increase.

- Australian Protective Domain Name System blocked over 67 million malicious domain requests, up 176 per cent.

- Domain Takedown Service blocked over 127,000 attacks against Australian servers, up 336 per cent.

- Cyber Threat Intelligence Sharing partners grew by 688 per cent to over 250 partners.

- Cyber Hygiene Improvement Program

- issued 103 High-priority Operational Taskings, up 110 per cent

- distributed around 4,900 reports to approximately 1,360 organisations, up 16 per cent and 32 per cent respectively.

- Critical Infrastructure Uplift Program (CI-UP) achieved

- 3 CI-UPs completed covering 6 CI assets

- 3 CI-UPs in progress

- 20 CI-UP Info Packs sent

- 5 CI-UP workshops held.

- Notified 7 critical infrastructure entities of suspicious cyber activity, up from 5 last year.

- Published or updated 34 PROTECT and Information Security Manual (ISM) guidance publications.

- Published 64 alerts, advisories, incident and insight reports on cyber.gov.au and the Partnership Portal.

- ASD’s Cyber Security Partnership Program grew to around 110,000 partners

- Individual Partners up 24 per cent

- Business Partners up 37 per cent

- Network Partners up 29 per cent.

- Led 20 cyber security exercises involving over 75 organisations to strengthen Australia’s cyber resilience.

- Briefed board members and company directors covering 33 per cent of the ASX200.

ASD is able to build a national cyber threat picture, in part due to the timely and rich reporting of cyber security incidents by members of the public and Australian business. This aggregation of cyber security incident data enables ASD to inform threat mitigation advice with the latest trends and threats posed by malicious cyber actors. Any degradation in the quantity or quality of information reported to ASD harms cyber security outcomes. Information reported to ASD is anonymised prior to it being communicated to the community.

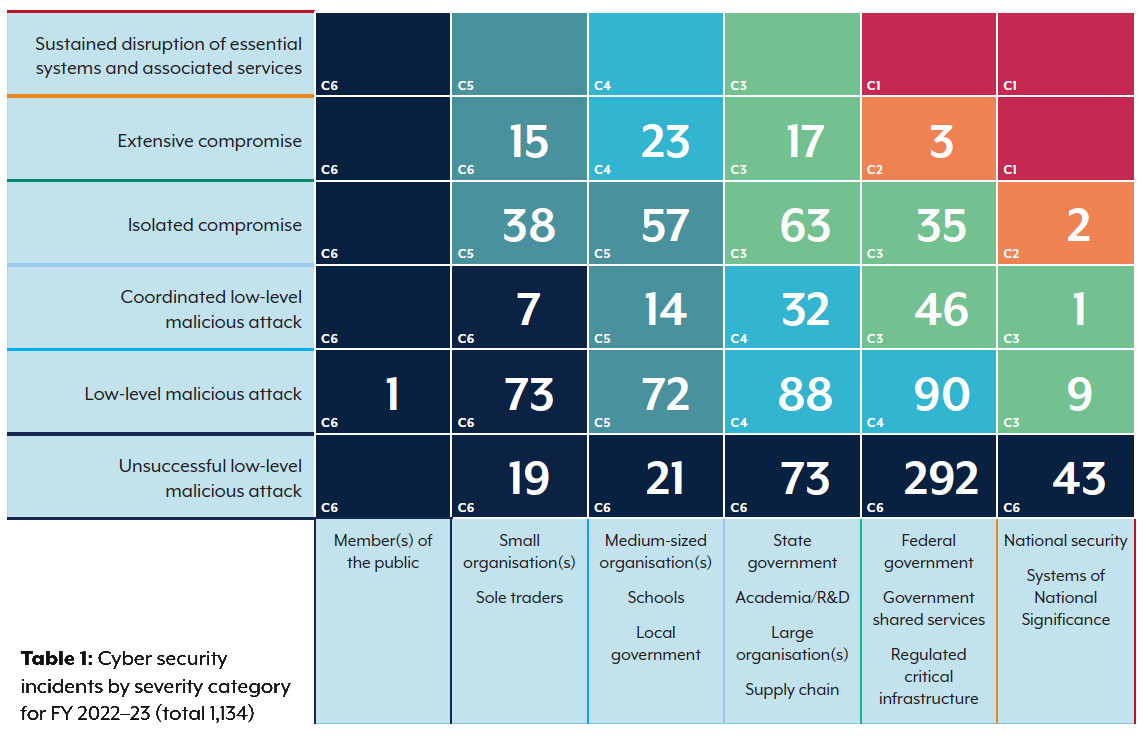

ASD categorises each incident it responds to on a scale of Category 1 (C1), the most severe, to Category 6 (C6), the least severe. Incidents are categorised on severity of effect, extent of compromise, and significance of the organisation.

The number of C2 incidents rose from 2 in FY 2021–22 to 5 in FY 2022–23. This includes significant data breaches involving cybercriminals exfiltrating data from critical infrastructure for the purposes of financial gain.

Cyber security incidents are consistent with last financial year, with around 15 per cent of all incidents being categorised C3 or above. Of the C3 incidents, over 30 per cent related to organisations self-identifying as critical infrastructure, with transport (21 per cent), energy (17 per cent), and higher education and research (17 per cent) the most affected sectors.

The most common C3 incident type was compromised assets, network or infrastructure (23 per cent), followed by data breaches (19 per cent) and ransomware (14 per cent). Common activities leading to C3 incidents included exploitation of public–facing applications (20 per cent) and phishing (17 per cent).

Almost a quarter (24 per cent) of C3 incidents involved a tipper, where ASD notified the affected organisations of suspicious activity.

While reports of low-level malicious attacks are often categorised as unsuccessful, reports of unsuccessful activity are still indicative of continual targeting of Australian entities.

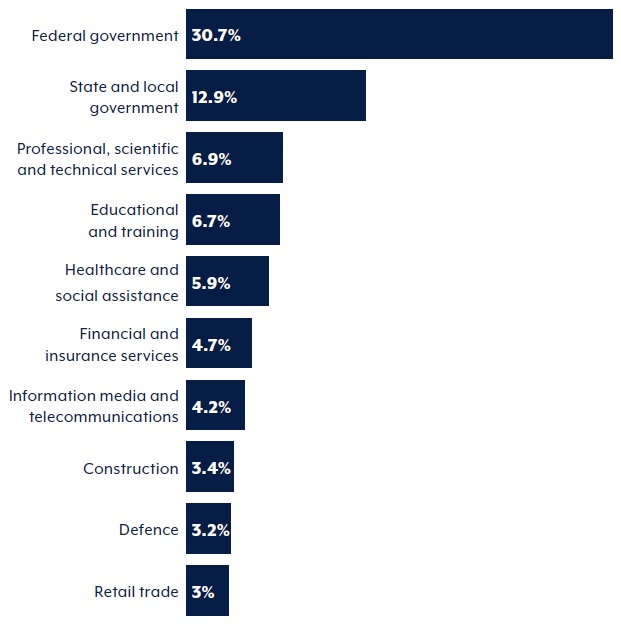

Cyber security incidents by sector

Compared to 2021–22, the information media and telecommunications sector fell out of the top 5 reporting sectors.

Government sectors and regulated critical infrastructure have reporting obligations, which may explain the relatively high reporting rate for these sectors compared with others.

ASD categorises sectors following the Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification (ANZSIC) Divisions from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. The public safety and administration division encompasses several sectors including federal, state, territory and local governments, public order and safety services, and Defence.

Table 3: The top 10 reporting sectors

Chapter 1: Exploitation

- Half of vulnerabilities were exploited within 2 weeks of a patch, or of mitigation advice being released, highlighting the risks entities take by not promptly patching.

- Patching vulnerabilities in internet-facing services should occur within 2 weeks, or 48 hours if an exploit exists.

- Vulnerable internet-facing devices and applications are convenient targets for malicious cyber actors. In addition to patching, unnecessary internet-facing services should be disabled.

Vulnerable and exposed

As Australians integrate more technology into their lives and businesses, the number of possible weak points or vectors for malicious cyber actors to exploit – known as the attack surface – grows. The larger the attack surface, the harder it is to defend. Malicious cyber actors often exploit security weaknesses found in ICT, known as common vulnerabilities and exposures (CVEs), to break into systems, steal data, or even take complete control over a system.

The number of published CVEs has been steadily on the rise. The US National Vulnerability Database published 19,379 CVEs in FY 2020–21, 24,266 CVEs in FY 2021–22, and 29,019 CVEs in FY 2022–23.

To identify the rates at which CVEs were exploited after a patch or mitigation was made available, ASD analysed 60 CVEs covering 1 July 2020 to 28 February 2023. The analysis found around 82 per cent of vulnerabilities had an attack vector of ‘network’ under the Common Vulnerability Scoring Scheme. This indicates that malicious actors prefer vulnerabilities that are remotely exploitable and are present on internet-facing or edge devices. Exploitation of these vulnerabilities allows malicious actors to pivot into internal networks. The analysis also found:

- 1 in 5 vulnerabilities was exploited within 48 hours of a patch or mitigation advice being released

- half of the vulnerabilities were exploited within 2 weeks of a patch or mitigation advice being released

- 2 in 5 vulnerabilities were exploited more than one month after a patch or mitigation advice was released.

Despite more than 90 per cent of CVEs having a patch or mitigation advice available within 2 weeks of public disclosure, 50 per cent of the CVEs were still exploited more than 2 weeks after that patch or mitigation advice was published. This highlights the risk entities carry when not patching promptly. These risks are heightened when a proof-of-concept code is available and shared online, as malicious cyber actors can leverage this code for use in automated tools, lowering the barrier for exploitation.

ASD observed that Log4Shell (CVE-2021-44228) and ProxyLogon (CVE-2021-26855) were by far the most commonly exploited vulnerabilities throughout the analysis period, with these 2 vulnerabilities representing 29 per cent of all CVE-related incidents.

CVEs do not have an expiration date. In one instance, ASD observed that malicious cyber actors successfully exploited an unpatched 7-year-old CVE. Additionally, ASD still receives periodic reports of WannaCry malware – 6 years after its release – which is likely due to old, infected legacy machines being powered on and connected to networks. Incidents like this highlight the importance of patching as soon as possible, and also demonstrate the long tail of risks that unpatched and legacy systems can pose to entities.

During 2022–23, ASD published many alerts warning Australians of vulnerabilities, such as the critical remote code execution vulnerability in Fortinet devices (CVE-2022-40684), and a high-severity vulnerability present in Microsoft Outlook for Windows (CVE-2023-23397). ASD also published a joint Five-Eyes advisory detailing the top 12 CVEs most frequently and routinely exploited by malicious cyber actors for the 2022 calendar year.

Patching

To help mitigate vulnerabilities, ASD recommends all entities patch, update or otherwise mitigate vulnerabilities in online services and internet-facing devices within 48 hours when vulnerabilities are assessed as critical by vendors or when working exploits exist. Otherwise, vulnerabilities should be patched, updated or otherwise mitigated within 2 weeks. Entities with limited cyber security expertise who are unable to patch rapidly should consider using a reputable cloud service provider or managed service provider that can help ensure timely patching.

ASD acknowledges not all entities may be able to immediately patch, update or apply mitigations for vulnerabilities due to high-availability business requirements or system limitations. In such cases, entities should consider compensating controls like disabling unnecessary internet-facing services, strengthening access controls, enforcing network separation, and closely monitoring systems for anomalous activity. Entities should ensure decision makers understand the level of risk they hold and the potential consequences should their systems or data be compromised as a result of a malicious actor exploiting unmitigated vulnerabilities.

Further patching advice can be found in ASD’s Assessing Vulnerabilities and Applying Patches guide.

Cyber hygiene

In addition to patching, effective cyber security hygiene is vital. At cyber.gov.au, ASD has published a range of easy-to-understand advice and guides tailored for individuals, small and medium business, enterprises, and critical infrastructure providers.

All Australians should:

- enable multi-factor authentication (MFA) for online services where available

- use long, unique passphrases for every account if MFA is not available, particularly for services like email and banking (password managers can assist with such activities)

- turn on automatic updates for all software – do not ignore installation prompts

- regularly back up important files and device configuration settings

- be alert for phishing messages and scams

- sign up for the ASD’s free Alert Service

- report cybercrime to ReportCyber.

Australian organisations should also:

- only use reputable cloud service providers and managed service providers that implement appropriate cyber security measures

- regularly test cyber security detection, incident response, business continuity and disaster recovery plans

- review the cyber security posture of remote workers, including their use of communication, collaboration and business productivity software

- train staff on cyber security matters, in particular how to recognise scams and phishing attempts

- implement relevant guidance from ASD’s Essential Eight Maturity Model, Strategies to Mitigate Cyber Security Incidents and Information Security Manual

- join ASD’s Cyber Security Partnership Program

- report cybercrime and cyber security incidents to ReportCyber.

Case study 1: Malicious cyber actors exploit devices 2 years after patch

On 24 May 2019, Fortinet, a US vendor that creates cyber security products, released a security advisory and accompanying patch for CVE-2018-13379, which was a severe vulnerability that required immediate patching.

On 2 April 2021, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) published an advisory on the exploitation of Fortinet FortiOS vulnerabilities, which indicated advanced persistent threat (APT) groups were scanning devices for CVE-2018-13379 and likely to gain access to multiple government, commercial, and technology services networks.

On 3 April 2021, ASD released an alert reminding organisations that APT groups had been observed exploiting CVE-2018-13379. Later, in September 2021, ASD received a report of a successful exploitation of CVE-2018-13379 against an Australian entity. Despite being vulnerable for more than 2 years, the victim’s device had not been patched.

While it is difficult to ascertain how widely Fortinet devices are used globally, researchers identified around 50,000 targets that remained vulnerable 2 years after the patch was released. This number is so significant that it was added to CISA’s Top Routinely Exploited Vulnerabilities list.

The primary mitigation against these attacks is to patch vulnerabilities as soon as possible. If patching is not immediately possible, the entity should consider removing internet access from Fortinet devices until other mitigations can be implemented.

Case study 2: A network compromise at the Shire of Serpentine Jarrahdale

The rural Shire of Serpentine Jarrahdale, 45 kilometres from the Perth CBD, may seem an unlikely place for malicious cyber activity to unfold. But, in early 2023, the Shire experienced a network compromise. Shire ICT Manager Matthew Younger said the malicious cyber actor took advantage of a public-facing system. ‘We’re quite diligent with our patching, but unfortunately we missed an update to our remote work server,’ Mr Younger said.

Before taking immediate remediation action, the Shire’s ICT team held a conference call with ASD to discuss the best way to manage the compromise, and Mr Younger said ASD’s help was first-class. ‘We put a perimeter around the compromised server, checked for lateral movement, and gathered evidence to work out what happened. Everything we found led back to the importance of the Essential Eight.’

ASD also sent an incident responder to help the Shire’s ICT team capture virtual machine snapshots and log data. ASD handles incident data with strict confidentiality, and such data helps its analysts understand how cyber security incidents occur and produces intelligence to help build the national cyber threat picture and to prevent further attacks.

Mr Younger said that after the compromise, the Shire doubled-down on its efforts to implement ASD’s Essential Eight. ‘We enforced passphrases, we improved our information security policies, and we improved our user security training. We also validated our controls through penetration testing and phishing exercises.’

Mr Younger credits much of the Shire’s success to its agile leadership who, with limited resources, foster the right security culture to both respond to cyber threats and implement mitigations.

CVE-2020-5902

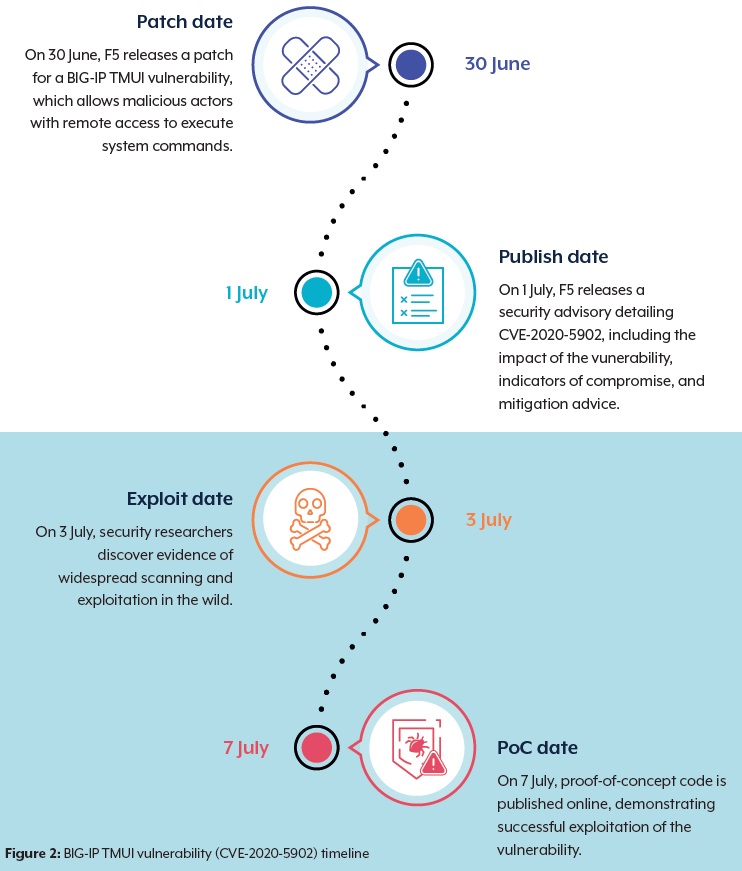

BIG-IP refers to a suite of products from cyber security vendor F5, which includes firewall and application delivery solutions. On 1 July 2020, F5 released a security advisory detailing a critical vulnerability in their BIG-IP Traffic Management User Interface (TMUI). Within 48 hours of patch release, security researchers discovered malicious cyber actors scanning for and exploiting unpatched devices.

The Essential Eight

ASD’s Essential Eight are some of the most effective cyber security mitigation strategies, and includes:

1. application control

1. application control

2. patch applications

2. patch applications

3. configure Microsoft Office macro settings

3. configure Microsoft Office macro settings

4. user application hardening

4. user application hardening

5. restrict administrative privileges

5. restrict administrative privileges

6. patch operating systems

6. patch operating systems

7. multi-factor authentication

7. multi-factor authentication

8. regular backups

8. regular backups

ASD uses its cyber threat intelligence to ensure its cyber security advice is contemporary and actionable. ASD’s advice is not formed in a silo. Feedback from partners across government and industry, such as how cyber security mitigations are implemented within organisations, is important. Feedback helps ASD update advice like the Essential Eight.

More information on the Essential Eight, including the Essential Eight Assessment Process Guide and Essential Eight Maturity Model Frequently Asked Questions, can be found at cyber.gov.au.

Chapter 2: Critical infrastructure

- During FY 2022–23, Australian critical infrastructure networks regularly experienced both targeted and opportunistic malicious cyber activity. Activity against these networks is likely to increase as networks grow in size and complexity.

- Malicious cyber actors can steal or encrypt data, or gain insider knowledge for profit or competitive advantage. Some actors may attempt to degrade or disrupt services and these incidents can have cascading impacts.

- Designing robust cyber security measures for operational technology environments is vital to protect the safety, availability, integrity and confidentiality of essential services. Secure-by-design and secure‑by-default products should be a priority.

Actors target critical infrastructure for many reasons

Critical infrastructure assets and networks are attractive targets for malicious cyber activity as these assets need to hold sensitive information, maintain essential services, and often have high levels of connectivity with other organisations and critical infrastructure sectors.

A cyber incident can result in a range of impacts to critical services. For instance, the disruption of an electricity grid could cause a region to lose power. Without power, a hospital may lose access to patient records and struggle to function, internet services may be down and affect communications and payment systems, or water supply could be impacted.

Globally, a broad range of malicious cyber actors, including state actors, cybercriminals and issue‑motivated groups, have demonstrated the intent and the capability to target critical infrastructure. Malicious cyber actors may target critical infrastructure for a range of reasons. For example, they may:

- attempt to degrade or disrupt services, such as through denial-of-service (DoS) attacks, which can have a significant impact on service providers and their customers

- steal or encrypt data or gain insider knowledge for profit or competitive advantage

- preposition themselves on systems by installing malware, in anticipation of future disruptive or destructive cyber operations, potentially years in advance

- covertly seek sensitive information through cyber espionage to advance strategic aims.

Critical infrastructure can be targeted by the mass scanning of networks for both old and new vulnerabilities. In February 2023, an Italian energy and water provider was affected by ransomware. While there was no indication the water or energy supply was affected, it reportedly took 4 days to restore systems like information databases. Italy’s National Cybersecurity Agency publicly noted the ransomware attack targeted older and unpatched software, exploiting a 2-year-old vulnerability.

Critical infrastructure is a target globally

During 2022–23, critical infrastructure networks around the world continued to be targeted, causing impacts on network operators and those relying on critical services. In the latter half of 2022, the French health system reportedly sustained a number of cyber incidents. One hospital fell victim to a ransomware incident, resulting in the cancellation of some surgical operations and forcing patients to be transferred to other hospitals. The hospital’s computer systems had to be shut down to isolate the attack.

Russia’s war on Ukraine has continued to demonstrate that critical infrastructure is viewed as a target for disruptive and destructive cyber operations during times of conflict. Malicious cyber actors have targeted and disrupted hospitals, airports, railways, telecommunication providers, energy utilities, and financial institutions across Europe. Destructive malware was also used against critical infrastructure in Ukraine.

In September 2022 and May 2023, ASD and its international partners published advisories highlighting that state actors were targeting multiple US critical infrastructure sectors, and strongly encouraged Australian entities to review their networks for signs of malicious activity. More details about these advisories is in the state actor chapter.

Australian critical infrastructure is impacted

Australian critical infrastructure networks regularly experienced both targeted and opportunistic malicious cyber activity. During 2022–23, ASD responded to 143 incidents reported by entities who self-identified as critical infrastructure, an increase from the 95 incidents reported in 2021–22. The vast majority of these incidents were low-level malicious attacks or isolated compromises.

The main cyber security incident types affecting Australian critical infrastructure were:

- compromised account or credentials

- compromised asset, network or infrastructure

- DoS.

These incident types accounted for approximately 57 per cent of the incidents affecting critical infrastructure for 2022–23. Other more prominent incident types were data breaches followed by malware infection.

ASD encourages critical infrastructure entities to report anomalous activity early and not wait until malicious activity reaches the threshold for a mandatory report. Reporting helps piece together a picture of the cyber threat landscape, and informs ASD’s cyber security alerts and advisories for the benefit of all Australian entities.

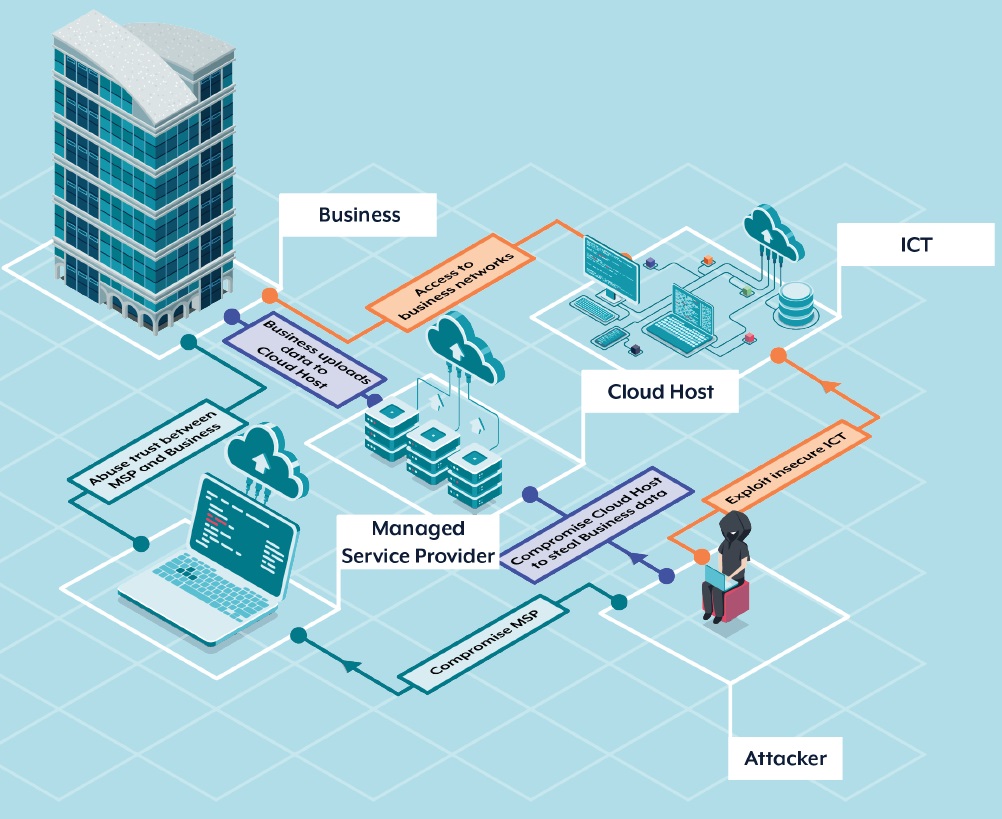

Critical infrastructure networks have a broad attack surface

The interconnected nature of critical infrastructure networks, and the third parties in their ICT supply chain, increases the attack surface for many entities. This includes remote access and management solutions, which are increasingly present in critical infrastructure networks.

Operational technology (OT) and connected systems, including corporate networks, will likely be of enduring interest to malicious cyber actors. OT can be targeted to access a corporate network and vice versa, potentially allowing malicious cyber actors to move laterally through systems to reach their target. Even when OT is not directly targeted, attacks on connected corporate networks can disrupt the operation of critical infrastructure providers.

Systems where software or hardware are not up to date with the latest security mitigations are vulnerable to exploitation, particularly when these systems are exposed to the internet. ICT supply chain and managed service providers are another avenue malicious cyber actors can exploit.

Explainer 1: Operational technology

OT makes up those systems that detect or cause a direct change to the physical environment through the monitoring or control of devices, processes, and events. OT is predominantly used to describe industrial control systems (ICS), which include supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems and distributed control systems (DCS).

Australian critical infrastructure providers often operate over large geographical areas and require interconnection between dispersed OT environments. Separately, remote access to OT environments from corporate IT environments and the internet has become standard operating procedure. Remote access allows engineers and technicians to remotely manage and configure the OT environment. However, this interconnection or remote access requires an internet connection, which creates additional cyber security risks to OT environments.

In April 2023, irrigation systems in Israel were reportedly disrupted when the ICS supporting the automated water controllers were compromised. Israel’s National Cyber Organisation was able to warn many farmers to disconnect their remote control option for the irrigation systems, so the disruption was minimal. Being able to disconnect from remote control also highlights the value of a manual override mechanism in some instances.

Next-generation OT is expected to contain built-in remote access and security features, which could address some of the issues related to remote access and internet exposure. ASD continues to advise entities to prioritise secure-by-design and secure-by-default products in procurements, and take a risk-based approach to managing risks associated with new technologies or providers. Good cyber security practices will be particularly important during a transition to new technologies.

At cyber.gov.au, ASD has published a range of cyber security guides for OT and ICS, and also principles and approaches to secure-by-design and default.

In focus: food and grocery sector

The food and grocery sector covers a broad supply chain including processing, packaging, importing, and distributing food and groceries. Food and grocery manufacturing is Australia’s largest manufacturing sector, comprising over 16,000 businesses and representing around 32 per cent of all manufacturing jobs. Food and grocery organisations are an attractive target for malicious cyber actors as this sector’s provision of essential supplies has little tolerance for disruption.

The sector’s complex supply chains and growing online sales mean food and grocery organisations have a large attack surface. The sector is increasingly reliant on smart technologies, industrial control systems, and internet-based automation systems. Additionally, many entities in this sector hold sensitive data that may be of value to malicious cyber actors, such as personal information or intellectual property.

Like other manufacturing entities, food and grocery organisations have increasingly adopted just-in-time inventory and delivery chains in pursuit of greater efficiency and reduced waste. This means the food and grocery sector is also vulnerable if a supplier is affected by a cyber incident that disrupts services.

Large entities in this sector may be targeted based on the view that they can be extorted for large sums of money. Smaller entities may be perceived as having lower cyber security maturity, and may be used to access more lucrative targets in their supply chain. Malicious cyber actors may seek to remain undetected on systems to establish a secure foothold and then move to other systems within a business to exfiltrate data or maintain a presence for future malicious activity.

A cyberattack against entities in this sector could have significant impacts for both the victim organisation and its customers. For example, a ransomware attack that locks systems could halt production and delivery, rendering a business unable to fulfil its orders. The second order impacts of this could be costly – including lost revenue, or lost confidence from business partners and customers alike.

Early detection of malicious activity is vital for mitigating cyber threats. It can take time to discover a compromised network or system, so robust and regular monitoring is essential. Likewise, practised incident response plans and playbooks should form part of broader corporate and cyber plans to aid remediation and minimise the impact of a compromise. Entities in this sector should seek secure-by-design and secure‑by-default products wherever possible to boost their cyber security posture.

A comprehensive list of resources for critical infrastructure is available at cyber.gov.au, including guidance for cyber incident response and business continuity plans.

Case study 3: Global food distributor held to ransom

In February 2023, Dole – one of the world’s largest producers and distributors of fruit and vegetables – was a victim of a ransomware incident, resulting in a shut down of its systems throughout North America. Other reported impacts included some product shortages, a limited impact on operations, and theft of company data – including some employee information. While Dole acted swiftly to minimise the impacts of the incident, it still reported USD $10.5 million in direct costs, and faced reputational damage.

Explainer 2: Effective separation

Separating network segments can help to isolate critical network elements from the internet or other less sensitive parts of a network. This strategy can make it significantly more difficult for malicious cyber actors to access an organisation’s most sensitive data, and can aid cyber threat detection.

In 2022–23, ASD observed that effective separation through network segmentation and firewall policies prevented malware from impacting an Australian critical infrastructure provider. Additionally, through effective separation an Australian critical infrastructure provider prevented the deployment of malware from a contractor’s USB drive onto their OT environment.

Network separation is more than just a logical or physical design decision: it should also consider where system administration and management services are placed. Often, the corporate IT network is separated from the OT environment, because the corporate IT network is usually seen as having a higher risk of compromise due to its internet connectivity and services like email and web browsing.

However, if a malicious cyber actor compromises the corporate IT network and gains greater access privileges, then the corporate IT firewall may no longer provide the desired level of protection for the OT environment. This similarly applies if the Active Directory (AD) Domain for the OT environment is inside an AD Forest administered from the corporate IT network.

Critical infrastructure operators should regularly assess the risk of insufficient separation of system administrative and management role assignments. For example, in scenarios where the virtualisation of OT infrastructure or components is managed by privileged accounts from a corporate domain, if the corporate environment was to become compromised then the OT environment would potentially be impacted and those necessary privileged IT accounts may not be accessible.

Case study 4: Horizon Power working with ASD

Western Australian energy provider Horizon Power distributes electricity across the largest geographical catchment of any Australian energy provider – around 2.3 million square kilometres, or roughly an area 4 times bigger than France. It operates a diverse range of OT and ICT infrastructure to manage around 8,300 kilometres of transmission lines and deliver power to more than 45,000 customers.

In early 2023, Horizon Power partnered with ASD to conduct a range of activities to help examine and test its cyber security posture and controls. Horizon Power’s security team worked side-by-side with ASD’s experts to help improve threat detection, security event triage and response; practice forensic artefact collection; and enhance security communication across the enterprise. The activities have helped to improve both the speed and the quality with which Horizon Power can respond to and manage cyber incidents, including sharing cyber threat intelligence with ASD.

Horizon Power Senior Technology Manager Jeff Campbell said engaging ASD was easy, there were clear objectives, and the network assessments were excellent. ‘Long past are the days of holding cards to our chest. Sharing information is really important across multiple industries and sectors. To improve security, you need to find out what you don’t know.’

Mr Campbell said having ASD onsite helped to test many assumptions about the company’s network security, like its segmentation practices and vulnerability management. 'The engagement highlighted the importance of getting visibility over systems, and also helped to demonstrate that effective cyber security is vital to helping mitigate business risks.'

Learn more about the open, collaborative partnership between Horizon Power and the Australian Signals Directorate that enabled Horizon Power to bolster its cyber security controls.

Building cyber resilience in critical infrastructure

Malicious cyber activity against Australian critical infrastructure is likely to increase as networks grow in size and complexity. Critical infrastructure organisations can do many things to reduce the attack surface, secure systems, and protect sensitive data to help ensure Australia’s essential services remain resilient. Such as:

- Follow best practice cyber security, like ASD’s Essential Eight, or equivalent framework as required for a critical infrastructure risk-management program.

- Thoroughly understand networks, map them, and maintain an asset registry to help manage devices on all networks, including OT. Consider the security capabilities available on devices as part of routine architecture and asset review, and the most secure approach to hard-coded passwords.

- Scrutinise the organisation’s ICT supply chain vulnerabilities and risks.

- Prioritise secure-by-design or secure-by-default products. Consider the security controls of any new software, hardware, or OT before it is purchased, and understand vendor support for future patches and ongoing security costs. Build cyber security costs into budgets for the entire lifecycle of the product, including the product’s replacement.

- Understand what is necessary to keep critical services operating and protect these systems as a priority. Ensure OT and IT systems can be, or are, segmented to ensure the service is able to operate during a cyber incident.

- Treat a cyber incident as a ‘when’ not ‘if’ scenario in risk and business continuity planning, and regularly practice cyber incident response plans.

- Maintain open communication with ASD. ASD has a number of programs to support critical infrastructure, including cyber uplift activities and cyber threat intelligence sharing.

- Follow ASD’s cyber security publications tailored for critical infrastructure entities available at cyber.gov.au.

Explainer 3: The Trusted Information Sharing Network

The Department of Home Affairs’ Trusted Information Sharing Network (TISN) takes an all-hazards approach to help build security and resilience for organisations within the Australian critical infrastructure community. To rapidly and flexibly address current and future threats to Australia’s security, the TISN allows for all levels of government and industry to connect and collaborate.

Since launching the TISN platform in 2022, the network has been vital in amplifying key messages and information to members, facilitating sector group meetings and contributing to the weekly Community of Interest meetings to inform members of current data breaches, cyber threats, and technical advice available from ASD.

Explainer 4: Resilience in financial services

CPS 230 Operational Risk Management

Events of recent years have demonstrated the critical importance of financial institutions being able to manage and respond to operational risks, evident for example in the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, technology risks and natural disasters. Sound operational risk management is fundamental to financial safety and system stability.

To ensure that all APRA-regulated entities in Australia are well placed to manage operational risk and respond to business disruptions when they inevitably occur, on 17 July 2023, APRA released the new Prudential Standard CPS 230 Operational Risk Management (CPS 230).

CPS 230 encompasses operational risk controls and monitoring, business continuity planning and the management of third-party service providers. The aim of the standard is to:

- strengthen operational risk management with new requirements to address weaknesses that have been identified in existing practices of APRA-regulated entities. This includes requirements to maintain and test internal controls to ensure they are effective in managing key operational risks

- improve business continuity planning to ensure that APRA-regulated entities are ready to respond to severe business disruptions, and maintain critical operations such as payments, settlements, fund administration and claims processing. It is important that all APRA regulated entities are able to adapt processes and systems to continue to operate in the event of a disruption and set clear tolerances for the maximum level of disruption they are willing to accept for critical operations

- enhance third-party risk management by extending requirements to cover all material service providers that APRA-regulated entities rely upon for critical operations or that expose them to material operational risk, rather than just those that have been outsourced.

The new standard also aims to ensure that APRA-regulated entities are well positioned to meet the challenges of rapid change in the industry and in technology more generally.

CPS 234 Information Security

As part of APRA’s Cyber Security Strategy, all regulated entities are required to engage an independent auditor to perform an assessment against CPS 234, APRA’s Information Security Prudential Standard. This is the largest assessment of its kind conducted by APRA.

By the end of 2023, more than 300 banks, insurers and superannuation trustees will have completed their assessment. Early insights, from the assessments completed so far, have identified a number of common weaknesses across the industry, including:

- incomplete identification and classification for critical and sensitive information assets

- limited assessment of third-party information security capability

- inadequate definition and execution of control testing programs

- incident response plans not regularly reviewed or tested

- limited internal audit review of information security controls

- inconsistent reporting of material incidents and control weaknesses to APRA in a timely manner.

A summary of these findings, along with guidance to address gaps, have been shared in a recent APRA Insight Article – Cyber Security Stocktake Exposes Gaps. Entities are encouraged to review the common weaknesses identified and incorporate relevant strategies and plans to address shortfalls in their own cyber security controls, governance policies and practices. APRA will continue to work with entities that do not sufficiently meet CPS 234 requirements, to lift the benchmark for cyber resilience across the financial services industry.

Chapter 3: State actors

- State cyber actors will likely continue to target government and critical infrastructure, as well as connected systems and their supply chains as part of ongoing cyber espionage and information‑gathering campaigns. They do not just want state secrets; businesses also hold valuable and sensitive information.

- Some state actors are willing to use cyber capabilities to destabilise and disrupt systems and infrastructure. They may preposition on networks of strategic value for future malicious activities.

- Government and industry partnerships are vital in boosting national cyber security and resilience against cyberattacks by state actors.

Strategic context

The global and regional strategic environment continues to deteriorate, which is reflected in the observable activities of some state actors in cyberspace. In this context, these actors are increasingly using cyber operations as the preferred vector to build their geopolitical competitive edge, whether it is to support their economies or to underpin operations that challenge the sovereignty of others. In the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation’s Annual Report 2021–22, espionage and foreign interference was noted to have supplanted terrorism as Australia’s principal security concern.

Some states are willing to use cyber capabilities to destabilise or disrupt economic, political and social systems. Some also target critical infrastructure or networks of strategic value with the aim of coercion or prepositioning on a network for future disruptive activity.

State actors have an enduring interest in obtaining information to develop a detailed understanding of Australians and exploit this for their advantage. While government information is an attractive target for state actors seeking strategic insights into Australia’s national policy and decisions, many Australian businesses also hold sensitive and valuable data such as proprietary information, research, and personal information. Unlike cybercriminals who may post stolen data in public forums, state actors usually try to keep their activities covert – seeking to remain unnoticed, both when they are on an entity’s network and after a compromise.

State actors use various tools and techniques

In some cases, state actors may develop bespoke tools and techniques to fulfil their operational aims. In May 2023, ASD released a joint cyber security advisory with its international partners on the Snake implant – a cyber espionage tool designed and used by Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) for long-term intelligence collection on high-priority targets around the globe. Shortly after, Australia co-badged another joint cyber security advisory with international partners that outlined malicious cyber activity associated with a People’s Republic of China (PRC) state-sponsored cyber actor.

Case study 5: Advisory – People’s Republic of China state-sponsored cyber activity

In May 2023, ASD joined international partners in highlighting a recently discovered cluster of activity associated with a PRC state-sponsored cyber actor, also known as Volt Typhoon. The campaign involved ‘living-off-the-land’ techniques – using built-in operating tools to help blend in with normal system and network activities. Private sector partners identified that this activity affected networks across US critical infrastructure sectors. However, the same techniques could be applied against critical infrastructure sectors worldwide, including in Australia.

ASD published the People’s Republic of China State-Sponsored Cyber Actor Living off the Land to Evade Detection advisory on cyber.gov.au and hosted numerous events to brief its Network Partners. For help to implement the advisory – call 1300 CYBER1 (1300 292 371).

Even when state actors have access to more advanced capabilities, they can use common tools and techniques to avoid the discovery of their best capabilities. For example, state actors continue to use relatively well-known tactics, such as exploiting unpatched or misconfigured systems and spear phishing.

The threat of state actor cyber operations is very real

State actors will likely continue to target government and critical infrastructure, as well as connected systems and their supply chains, as part of ongoing cyber espionage and information-gathering campaigns. Significant disruptive and destructive activities could occur if there were a major deterioration in Australia’s geopolitical environment. It is clear that preventative cyber security measures – such as implementing cyber security essentials, information-sharing and national cyber cooperation – are by far the best ways to help secure Australian networks.

In focus: Russia’s war on Ukraine

Cyber operations have been used alongside more conventional military activities during Russia’s war on Ukraine. Both Russia and Ukraine have faced many cyberattacks that impacted their societies, with extensive targeting of government and critical infrastructure networks.

Cyberattacks that began before the invasion of Ukraine have continued into 2023. Between January 2022 and the first week of February 2023, the Computer Emergency Response Team-Europe (CERT-EU) identified and analysed 806 cyberattacks associated with Russia’s war on Ukraine.

There has been extensive cyber targeting of Ukrainian networks across many sectors, including finance, telecommunications, energy, media, military and government. Ukraine has faced ransomware, denial‑of‑service (DoS) attacks, and mass phishing campaigns against critical infrastructure, government departments, officials and private citizens.

Russia has also been subject to cyber operations. Russian authorities have reported some of its federal agencies’ websites, including its energy ministry, were compromised by unknown attackers in a supply chain attack. Cyberattacks against Russia have tended to target entities related to the government, military, banking, logistics, transport and energy sectors.

Cyberattacks in Europe associated with Russia’s war on Ukraine

Figure 3: Countries impacted by cyberattacks associated with Russia’s war on Ukraine

Cyber operations have enabled a borderless conflict

Cyber operations associated with Russia’s invasion have affected entities in multiple countries during the first year of the conflict, including the European Parliament, European governments, the Israeli Government, and hospitals in the Netherlands, Germany, Spain, the US, and the UK. Many of these countries have linked the attacks to pro-Russian groups. For example, pro-Russian hacktivists, KillNet, have claimed a number of attacks such as the February 2023 DoS attack on numerous German websites, including those for German airports, public administration bodies, financial sector organisations, and other private companies. Belarus also reported its railway network was disrupted by a cyberattack, allegedly as retaliation for its use in transporting Russian troops. In some cases, Australia–based operations of European organisations have been impacted.

Many cyber actors are involved in the conflict in offence and defence

The mix of state and non-state cyber actors participating in Russia’s war on Ukraine has added to an already complex cyberspace domain. While state actors were on the ‘cyber front’, particularly during the earlier stages of the conflict, there was significant activity by hacktivists from around the globe as the conflict progressed. Regardless of whether a malicious cyber actor was a state, state-sponsored, or a non-state actor acting of their own volition, the scale and frequency of malicious cyber activity during the conflict has challenged cyber defenders on all sides. For example, at least 8 variants of destructive malware were identified in the first 6 weeks of the conflict, including wiper malware designed to erase data or prevent computers from booting.

Both state and non-state cyber actors have been on the offensive and defensive. Ukraine’s networks have been resilient and have largely withstood sustained cyberattacks. Ukraine has said this resilience is due to robust defences developed following previous cyberattacks, as well as partnerships with private sector IT companies. For example, with the support of private companies, Ukrainian government data was migrated to cloud infrastructure, which assured continuity of government services. Private companies also rapidly released threat intelligence, like indicators of compromise, to assist cyber defenders to repel network attacks.

Threat intelligence that might impact Australian entities is obtained by ASD through international partners and shared through cyber.gov.au and ASD’s Cyber Security Partnership Program.

Cyber operations can cause disruption and destruction in conflict

While the conflict remains ongoing, there are many lessons Australia can learn from Russia’s war on Ukraine. The world is witnessing the destructive impact of cyber operations during conflict, or in the pursuit of a state’s national interests, and how a broad range of critical infrastructure can be disrupted as a result of malicious cyber activity. It also demonstrates the impact non-state participants can have in modern conflict. The conflict has exemplified how government and industry partnerships are critical to boosting national cyber security and resilience.

Case study 6: The CTIS community at work – KillNet

The Cyber Threat Intelligence Sharing (CTIS) platform, operated by ASD, was developed with industry, for Australian Government and industry partners to build a comprehensive national threat picture and empower entities to defend their networks. CTIS allows participating entities to share indicators of compromise (IOCs) bilaterally at machine speed. Participating entities can use these IOCs to identify and block activity on their own networks, and share IOCs observed on their own networks with other CTIS partners.

The number of partners using CTIS increased seven-fold over 2022–23:

- in July 2022 there were 32 CTIS partners (18 consuming, 14 contributing)

- in June 2023 there were 252 CTIS partners (165 consuming, 87 contributing)

- by the end of FY 2022–23, CTIS shared 50,436 pieces of cyber threat intelligence

- as of 2023, ASD is progressing a further 313 candidate organisations for on-boarding.

In March 2023, a CTIS partner shared almost 1,000 IP addresses relating to a distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack on an Australian organisation. The partner linked the DDoS attack to the malicious cyber actor KillNet, a well-known pro-Russian hacktivist group. Since Russia’s war on Ukraine began, KillNet’s focus had been primarily Europe; however, recent trends suggest a shift to countries abroad, including Australia and its critical infrastructure.

CTIS partner contributions help participants defend their networks, and inform ASD’s understanding of threat actors, their motives and their tactics, techniques, and procedures. This information also helps ASD to identify trends within and across sectors.

For more information on CTIS, visit cyber.gov.au and become a Network Partner. Existing Network Partners can register their interest in accessing CTIS by either clicking on the ‘Register your interest’ button via the ASD Partnership Portal, or by contacting acsc.services@defence.gov.au.

Chapter 4: Cybercrime

- Profit-driven cybercriminals continually seek new ways to maximise payment and minimise their risk, including by changing their tactics and techniques to mask their actions and extract payment from victims.

- Ransomware remains the most destructive cybercrime threat to Australians, but is not the only cybercrime. Business email compromise (BEC), data theft, and denial-of-service (DoS) continue to impose significant costs on all Australians.

- Building a national culture of cyber literacy, practicing good cyber security hygiene, and remaining vigilant to cybercriminal activity – both at work and at home – will help make it harder for cybercriminals to do business.

Cybercrime is big business and causes harm

Cybercrime is a multibillion-dollar industry that threatens the wellbeing and security of every Australian. Cybercrime covers a range of illegal activities such as data theft or manipulation, extortion, and disruption or destruction of computer-dependant services. In 2022–23, cybercrime impacted millions of Australians, including individuals, businesses and governments. These crimes have caused harm and continue to impose significant costs on all Australians.

The Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) found, in its Cybercrime in Australia 2023 report, that individual victims and small-to-medium businesses experience a range of harms from cybercrime that extend beyond financial costs, such as impacts to personal health and legal issues. Cybercrime remains significantly underreported in Australia. The AIC’s report revealed that two-thirds of survey respondents had been victims of cybercrime in their lifetimes.

ASD needs community assistance to understand the cyber threat landscape. Australians are encouraged to report cyber security incidents and cybercrime to ReportCyber. ReportCyber is the Australian Government’s online cybercrime reporting tool coordinated by ASD and developed as a national initiative with state and territory police. ReportCyber may link Australians to other Australian Government entities for further support.

Cybercrime in 2022–23

The number of extortion-related cyber security incidents ASD responded to increased by around 8 per cent compared to last financial year.

Over 90 per cent of these incidents involved ransomware or other forms of restriction to systems, files or accounts.

ASD responded to 79 cyber security incidents involving DoS and DDoS, which is more than double the 29 incidents reported to ASD last financial year.

Cybercrime types

Cybercrime reports by state and territory

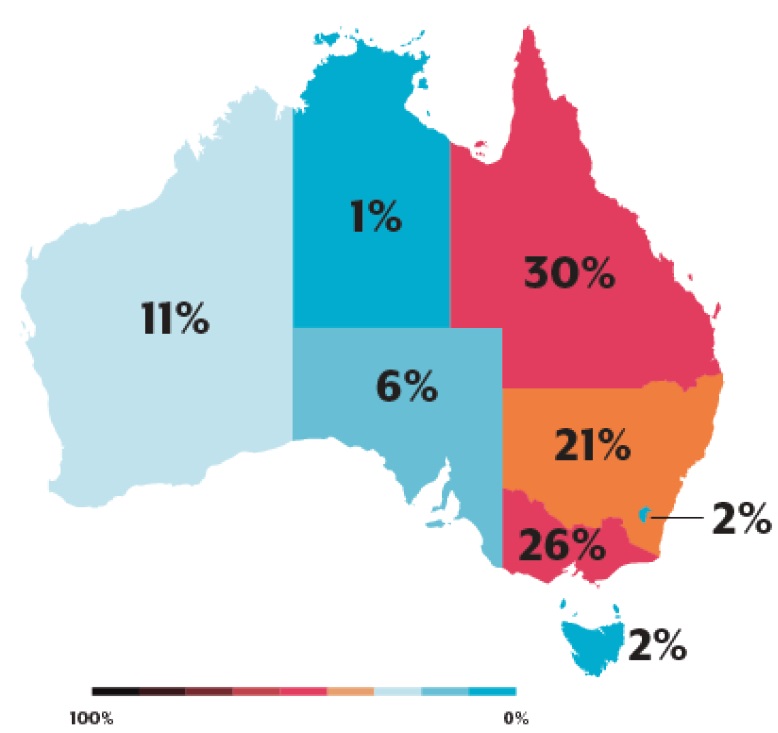

Australia’s more populous states continue to report more cybercrime. Queensland and Victoria report disproportionately higher rates of cybercrime relative to their populations. However, the highest average reported losses were by victims in New South Wales (around $32,000 per cybercrime report where a financial loss occurred) and the Australian Capital Territory (around $29,000).

Figure 4: Breakdown of cybercrime reports by jurisdiction for FY 2022–23

Note: Approximately one per cent of reports come from anonymous reporters and other Australian territories. Data has been extracted from live datasets of cybercrime and cyber security reports reported to ASD. As such, the statistics and conclusions in this report are based on point-in-time analysis and assessment.

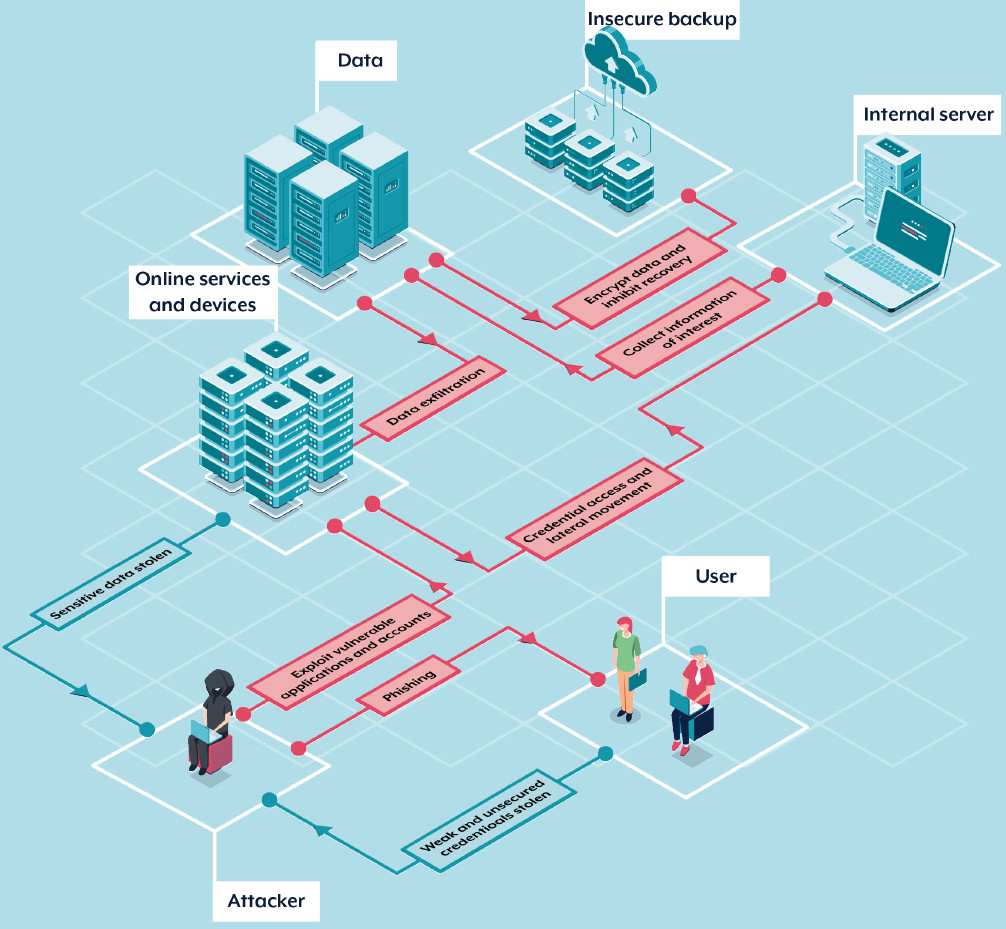

How criminals monetise access

Profit-driven cybercriminals continually seek new ways to maximise payment and minimise their risk, including by changing their tactics and techniques to mask their actions and extract payment from victims. Their targeting is largely opportunistic but can also be aimed at specific entities or individuals.

The professionalisation of the cybercrime industry means cybercriminals have been able to increase the scale and profitability of their activities. For example, initial access brokers sell their services and accesses to other malicious cyber actors who then use techniques, such as ransomware or data-theft extortion, to target victims. The accessibility of criminal marketplaces has also lowered the bar for entry into cybercrime, which has made cybercrime more accessible to a wide range of actors.

To gain initial access, cybercriminals may send multiple malicious links to a broad list of people (known as a phishing campaign), or scan for unpatched and misconfigured systems. Once they compromise a network, they may seek to move laterally through the network to gain access to higher-value systems, information or targets.

Cybercriminals may draw on a number of techniques to extract payment from victims, including employing multiple techniques at once – known as double or multiple extortion. While ransomware is a well-known technique, cybercriminals can monetise access to compromised data or systems in many different ways. They may scam a business out of money or goods, extort victims in return for decrypting data or non‑publication of data, on-sell compromised data or systems access for profit, or exploit compromised data or systems for future use.

Social engineering: how criminals get a foothold

Social engineering is a way in which cybercriminals can gain unauthorised access to systems or data by manipulating a person. They may do this by creating a sense of urgency or desire to help, or by impersonating a trusted source to convince a victim to click on a malicious link or file, or reveal sensitive information through other means – such as over the phone.

Phishing is one of the most common and effective techniques used by cybercriminals to gain unauthorised access to a computer system or network, and this activity may be indiscriminate or targeted. Once a victim engages with the malicious link or file, they may be prompted to provide personal details, or malware may run on their device to covertly retrieve this information. Cybercriminals may then use this information to steal money or goods, or leverage this information to access other accounts and systems of higher value.

Australians are becoming more aware of techniques dependent on social engineering, like phishing, but more can be done to build resilience:

- think twice before clicking on links from unsolicited correspondence

- verify the legitimacy of suspicious messages with the source via their official website or verified contact information, particularly if it is a request to transfer money or supply sensitive information. Visit the entity’s website directly, rather than via links in emails, SMS or other messaging services

- report unusual activity as quickly as possible to ReportCyber and Scamwatch

- educate staff on corporate-focused social engineering tactics and how to identify risk.

Explainer 5: Common cybercriminal techniques

Phishing is an attempt to trick recipients into clicking on malicious links or attachments to harvest sensitive information, like login details or bank account details, or to facilitate other malicious activity. Spear phishing is more targeted and tailored: cybercriminals may research victims using social media and the internet to craft convincing messages designed to lure specific victims.

Ransomware is a type of extortion that uses malware for data or system encryption. Cybercriminals encrypt data or a system and request payment in return for decryption keys. Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) is a business model between ransomware operators and ransomware buyers known as ‘affiliates’. Affiliates pay a fee to RaaS operators to use their ransomware, which can enable affiliates with little technical knowledge to deploy ransomware attacks.

Data-theft extortion does not require data encryption, but cybercriminals will use extortion tactics such as threatening to expose sensitive data to extract payment. The added threat of reputational damage is intended to pressure a victim into complying with the malicious cyber actor’s demands.

Data theft and on-sale is when data is extracted for use by a cybercriminal for the purpose of on-selling the data (such as personal information, logins or passwords) for further criminal activity, including fraud and financial theft. Some malware known as an ‘infostealer’ can do this job for the cybercriminal.

Business email compromise (BEC) is a form of email fraud. Cybercriminals target organisations and try to scam them out of money or goods by attempting to trick employees into revealing important business information, often by impersonating trusted senders. BEC can also involve a cybercriminal gaining access to a business email address and then sending out spear phishing emails to clients and customers for information or payment.

Denial-of-service (DoS) is designed to disrupt or degrade online services, such as a website. Cybercriminals may direct a large volume of unwanted traffic to consume the victim network’s bandwidth, which limits or prevents legitimate users from accessing the website.

Ransomware is a destructive cybercrime

Ransomware remains the most destructive cybercrime threat in 2022–23 to Australian entities. ASD recorded 118 ransomware incidents – around 10 per cent of all cyber security incidents.

A quarter of the ransomware reports also involved confirmed data exfiltration, also known as ‘double extortion’, where the actor extorts the victim for both data decryption and the non-publication of data. Other ransomware actors claimed to have exfiltrated data, but it is difficult to validate these claims until data exfiltration is confirmed or the legitimacy of leaked data is confirmed.

Ransomware is deliberatively disruptive, and places pressure on victims by encrypting and denying access to files. A ransom, usually in the form of cryptocurrency, is then demanded to restore access. This can inhibit entities, particularly those that rely on computer systems to operate and undertake core business functions.

Customers may also be impacted if they rely on the goods or services from that entity, or if their data is impacted. For example, in January 2023, cybercriminals reportedly compromised the postal service in the UK, encrypting files and disrupting international shipments for weeks. In other instances, ransomware incidents have had cascading impacts, sparking panic buying, fuel shortages, and medical procedure cancellations.

ASD advises against paying ransoms. Payment following a cybercrime incident does not guarantee that the cybercriminals have not already exfiltrated data for on-sale and future extortion.

ASD’s incident management capabilities provide technical incident response advice and assistance to Australian organisations. Further information can be found in the How the ASD's ACSC Can Help During a Cyber Security Incident guide.

Case study 7: Ransomware in Australia

In late 2022, an Australian education institution was impacted by the Royal ransomware, which is likely associated with Russian-speaking cybercrime actors. Royal ransomware restricts access to corporate files and systems through encryption. Notably, it uses a technique called ‘callback phishing’, which tricks a victim into returning a phone call or opening an email attachment that persuades them to install malicious remote access software.

When the institution detected the ransomware, it shut down some of its IT systems to stop the spread, which resulted in limited service disruption. An investigation revealed that a limited amount of personal information of both students and staff was compromised. The institution notified affected individuals and reminded them to remain vigilant for suspicious emails or communication. The institution also advised all students and staff to reset their passwords and introduced an additional verification process for remote users.

An ICT manager from the institution said downtime from the incident was minimal due to an effective business continuity plan and access to regular backups, which were unaffected by encryption. After the incident, the institution began moving toward more secure data storage methods.

The ICT manager said the incident highlighted how ubiquitous data is in an enterprise environment. ‘There were no crown jewels affected, so to speak. Important data was spread across the network. This incident taught us some lessons in relation to account management, and the regular review and archival of data’.

In January 2023, ASD published to cyber.gov.au the Royal Ransomware Profile, which describes its tactics, techniques and procedures and outlines mitigations. The ransomware profile was informed by cyber threat intelligence that the education institution shared with ASD.

Sectors impacted by ransomware-related cyber security incidents

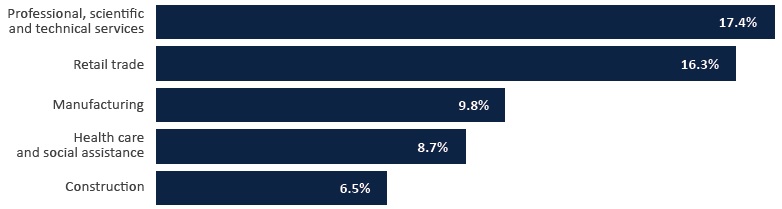

The professional, scientific and technical services sector reported ransomware-related cyber security incidents most frequently to ReportCyber in 2022–23, followed by the retail trade sector, then the manufacturing sector. These 3 sectors accounted for over 40 per cent of reported ransomware-related cyber security incidents.

Table 5: Top 5 sectors reporting ransomware-related incidents in FY 2022–23 (ReportCyber data)

Entities should consider how a ransomware incident could impact their business and their customers. To help prevent a ransomware attack, it is important to secure devices by turning on multi-factor authentication (MFA), implementing access controls, performing and testing frequent backups, regularly updating devices, and disabling Microsoft Office macros. It is also equally important to practice incident response plans to minimise the impact in the event of a successful ransomware incident.

Business email compromise is lucrative

BEC is an effective and lucrative technique that exploits trust in business processes and relationships for financial gain. Cybercriminals can compromise the genuine email account of a trusted sender, or impersonate a trusted sender, to solicit sensitive information, money or goods from businesses partners, customers or employees.

For example, a cybercriminal may gain access to the email account of a business and send an invoice with new bank account details to a customer of that business. The customer pays the invoice using the fraudulent bank account details provided by the cybercriminal, which is often thousands of dollars. A compromised business may only detect BEC once a customer has paid cybercriminals.

In 2022–23, the total self-reported BEC losses to ReportCyber was almost $80 million. There were over 2,000 reports made to law enforcement through ReportCyber of BEC that led to a financial loss. On average, the financial loss from each BEC incident was over $39,000.

Before replying to requests seeking money or personal information, look out for changes such as a new point-of-contact, email address or bank details. Simple things like calling an existing contact or the trusted sender to verify a request for money or change of payment details can help to prevent BEC.

Explainer 6: Business email compromise advice

Organisations should implement clear policies and procedures for workers to verify and validate requests for payment and sensitive information. Additionally:

- Register additional domain names to prevent typo-squatting – cybercriminals may create misleading domain names based on common typographic errors of a website, hoping its customers do not notice. Further information on Domain Name System Security for Domain Owners is available at cyber.gov.au.

- Set up email authentication protocols business domains – this helps prevent email spoofing attacks so that cybercriminals cannot wear a ‘digital mask’ pretending to be legitimate.

ASD has published the Preventing Business Email Compromise guide to help Australian organisations understand and prevent BEC.

Case study 8: Scams in Australia

In April 2023, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) released its Targeting Scams report. The report, which compiles data reported to the ACCC’s Scamwatch, ReportCyber, the Australian Financial Crimes Exchange, IDCARE and other government agencies, provides insight into the scams that impacted Australians in 2022. The report also outlines some of the activities by government, law enforcement, the private sector and community to disrupt and prevent scams.

The Targeting Scams report revealed Australians lost over $3 billion to scams in 2022. This is an 80 per cent increase on total losses recorded in 2021.

Investment scams were the highest loss category ($1.5 billion), followed by remote access scams ($229 million) and payment redirection scams ($224 million).

The most reported contact method used by scammers was text message; however, scam phone calls accounted for the highest reported losses. The second highest reported losses were from social media scams.

Older Australians lost more money to scams than other age groups with those aged 65 and over losing $120.7 million, an increase of 47.4 per cent from 2021. First Nations Australians, Australians with disability, and Australians from culturally and linguistically diverse communities each experienced increased losses to scams when compared with data from 2021.

On 1 July 2023, the Government launched the National Anti-Scam Centre. The Anti-Scam Centre will expand on the work of the ACCC’s Scamwatch service and bring together experts from government agencies, the private sector, law enforcement, and consumer groups to make Australia a harder target for scammers.

Hacktivists are using cyberattacks to further their causes

Hacktivism is used to describe a person or group who uses malicious cyber activity to further social or political causes, rather than for financial gain.

These malicious cyber actors, which include issue-motivated groups, are typically less capable, less organised, and less resourced than other types of malicious cyber actors. That said, even rudimentary disruptive activity – such as website defacement, hijacking of official social media accounts, leaking information, or DoS – can cause significant harm, reputational damage, and operational impacts to targeted entities.

Like cybercriminals, hacktivists may leverage malicious tools and services online to gain new capabilities and improve their ability to degrade or disrupt services for their cause.

Case study 9: Australian critical infrastructure targeted by issue-motivated DDoS

In March 2023, ASD became aware of reports of issue-motivated groups (hacktivists) targeting Australian organisations. Open source reporting linked the targeting of over 70 organisations to religiously motivated hacktivists.

The malicious activity commenced on 18 March with the defacement of, and/or DDoS against, the websites and other internet-facing services of small-to-medium businesses. This progressed to DDoS activity targeting the websites of Australian critical infrastructure entities, with multiple hacktivist groups announcing support for the campaign and publishing ‘target lists’ across a variety of platforms.

ASD received several incident reports from organisations experiencing hacktivist activity, including critical infrastructure providers. However, there was no impact on critical infrastructure operations, as only public-facing websites were affected. ASD provided advice and support to organisations, including by identifying IP addresses related to the attacks. ASD also shared indicators of compromise with its Network Partners.

In addition to ASD support, critical infrastructure providers worked closely with commercial incident-response providers and their in-house incident-response teams. One critical infrastructure provider identified through open source research that a second DDoS attack was being planned against their servers.

To prevent this attack, administrators enabled geo-blocking – where traffic from specific geolocations known to be used by the malicious cyber actor were blocked – to limit malicious traffic. This simple tactic helped the organisation avoid a second attack. As a result, the organisation did not suffer from any additional downtime.